Research

2017

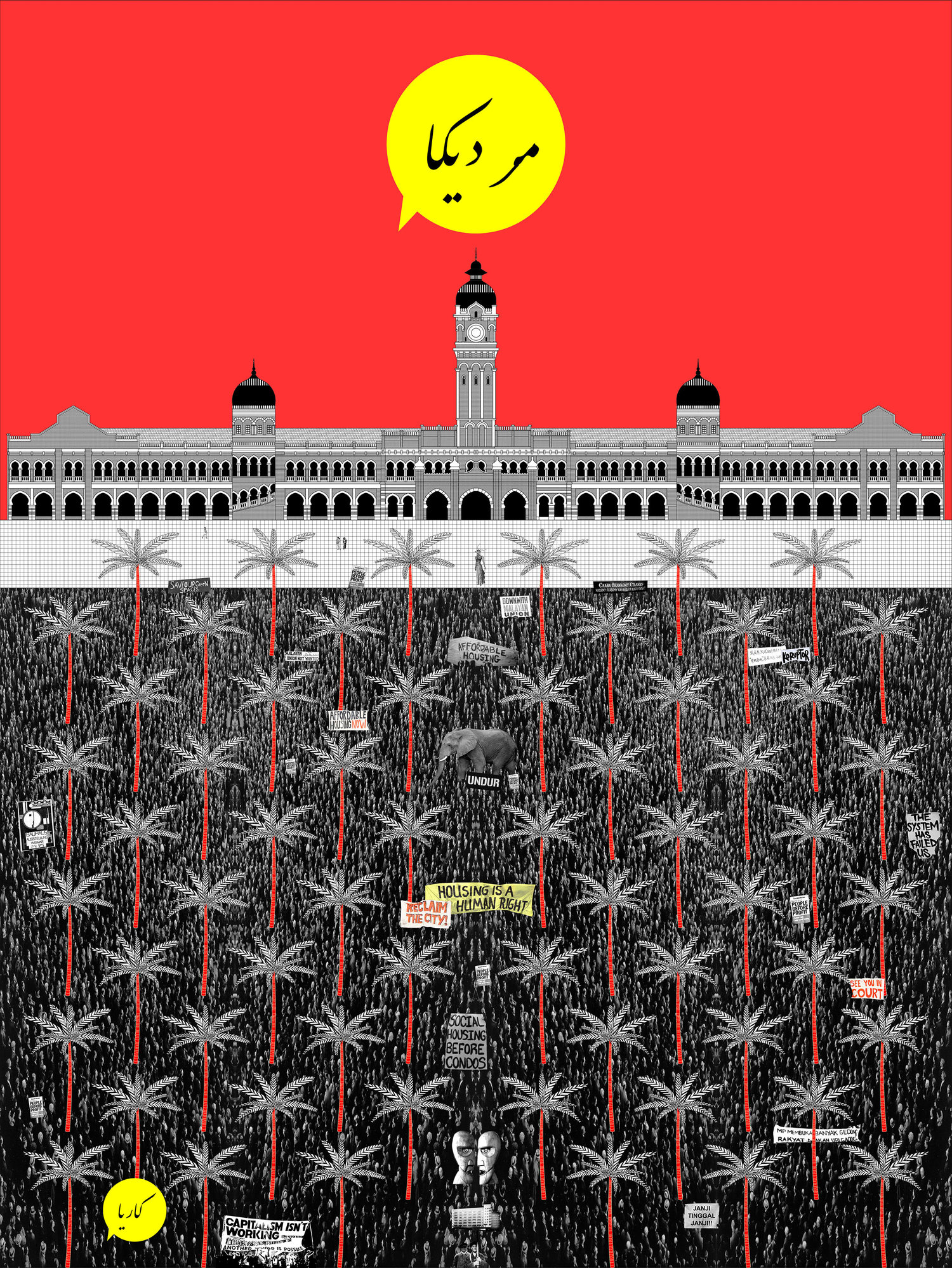

Dataran Merdeka as what it is called now was formally known as ‘the Padang’ which in Malay literally means a large turfed field with an area bigger than a football pitch or an open space where all sorts of activities could take place. The idea of this essay is not to educate the general public about the history of the Padang, but it is a call to liberate our understanding and thoughts to reclaim the people’s right over the city. Furthermore this essay must be read with an open mind; the critical analysis on the establishment is purely for the sake of creating meaningful discourse on architecture and social issues. The Padang plays a very emblematic role to Malaysia’s democracy since it was the very place where the whole nation gathered to witness the lowering of the Great Britain’s Union Jack Flag on midnight of 31st August 1957. The act itself was a very powerful form of expression by the people in reclaiming their rights to the city and to the country. It is powerful because it was the first time the people could demonstrate their freedom of expression openly which is a fundamental right in a democratic and independent country. Inspired by Henri Lefebvre’s the Right to the City, we have chosen to briefly analyse what is the current role of the Padang as it is now compared to what it was before.

2017

Dataran Merdeka as what it is called now was formally known as ‘the Padang’ which in Malay literally means a large turfed field with an area bigger than a football pitch or an open space where all sorts of activities could take place. The idea of this essay is not to educate the general public about the history of the Padang, but it is a call to liberate our understanding and thoughts to reclaim the people’s right over the city. Furthermore this essay must be read with an open mind; the critical analysis on the establishment is purely for the sake of creating meaningful discourse on architecture and social issues. The Padang plays a very emblematic role to Malaysia’s democracy since it was the very place where the whole nation gathered to witness the lowering of the Great Britain’s Union Jack Flag on midnight of 31st August 1957. The act itself was a very powerful form of expression by the people in reclaiming their rights to the city and to the country. It is powerful because it was the first time the people could demonstrate their freedom of expression openly which is a fundamental right in a democratic and independent country. Inspired by Henri Lefebvre’s the Right to the City, we have chosen to briefly analyse what is the current role of the Padang as it is now compared to what it was before.

We were intrigued to understand how within the span of 60 years, the urban commons are generally shrinking and being taken over by space and properties owned by private corporations. How could the most historical and significant public space in Malaysia be turned into an underground shopping mall with car parking bays. The worst part of all is the adoption of this trend by other public municipalities across the country i.e Dataran Pahlawan in Bandar Hilir Melaka. It was the ground for the first proclamation of independence in 1957 but was demolished for a commercial development. The challenge here is how to call for the people to reclaim their rights to the city by reclaiming the public spaces as genuine spaces that could contribute to nation-building and not more attempts by corporations to make money for themselves. A public space is not only a place of joyful celebration. It is also a ground for heartbroken communion, civic discussion and a place to exercise the right of assembly and free speech which is essential to participatory democracy.

Naive Democracy

The problem emerges when there is an extreme contradiction between the ideas of a ceremonial open space to commemorate the birth of democracy in Malaysia and that this same space should not be used for peaceful demonstration to express views and demands for rights – which forms the virtue of a democratic country with freedom of speech. This contradiction is the result of lack of understanding on true democracy. If only the people and the leaders truly understood democracy, they would agree that the right to reclaim urban commons is the right of the people, the right to freedom of speech is the right of the people, and the right to have basic urban goods is the right of the people. Why these urban commons are so inevitably important in a democratic society is simply because it differ a democratic society from an authoritarian society. Apart from being venues for official national events, the Padang had also witnessed a lot of other unofficial important events. In 1974 for instance, a massive rally was organised by university students demanding the government to take action on the issue of hunger and rural poverty in Baling, Sik, Selama and Changloon in Kedah. The demonstration was a success to emphasise the students 'movements’ demands, resulting in an almost immediate action taken by the government to help rural poverty issues throughout the nation.

This is an evidence on how the Padang, as a prominent public space in the country, played its role as urban commons where people could voice out opinions as what had been envisioned in the ‘The Right to the City’ – despite the fact that the aftermath of these series of demonstration was a more authoritarian approach towards handling student activism by the government. The rally organised by the university students became an impetus for the Padang to become the platform for other individuals and organisations who wanted to make an impact with their cause especially after the late 1990’s. We can’t deny the fact that the Reformasi Movement in 1998 had a huge impact on giving a wake-up call to the general public on their rights to participate and demonstrate freedom of speech. In recent years, more demonstration took place at the Padang, amongst the most commonly known are Bersih, Occupy Dataran, and some other demonstrations on various political issues. This proved that the Padang is still relevant as urban commons where people could demonstrate their rights. However, it was interesting to note that the recent Bersih demonstration in 2016 witnessed the protestors utilising the Padang and KLCC, despite KLCC being a privately-owned space. This is simply because the Padang was fully guarded by the police. The people might have successfully gathered to protest and expressed their rights but for that particular occasion the people had failed to reclaim their rights to the Padang and had resorted to make use of a private land instead.

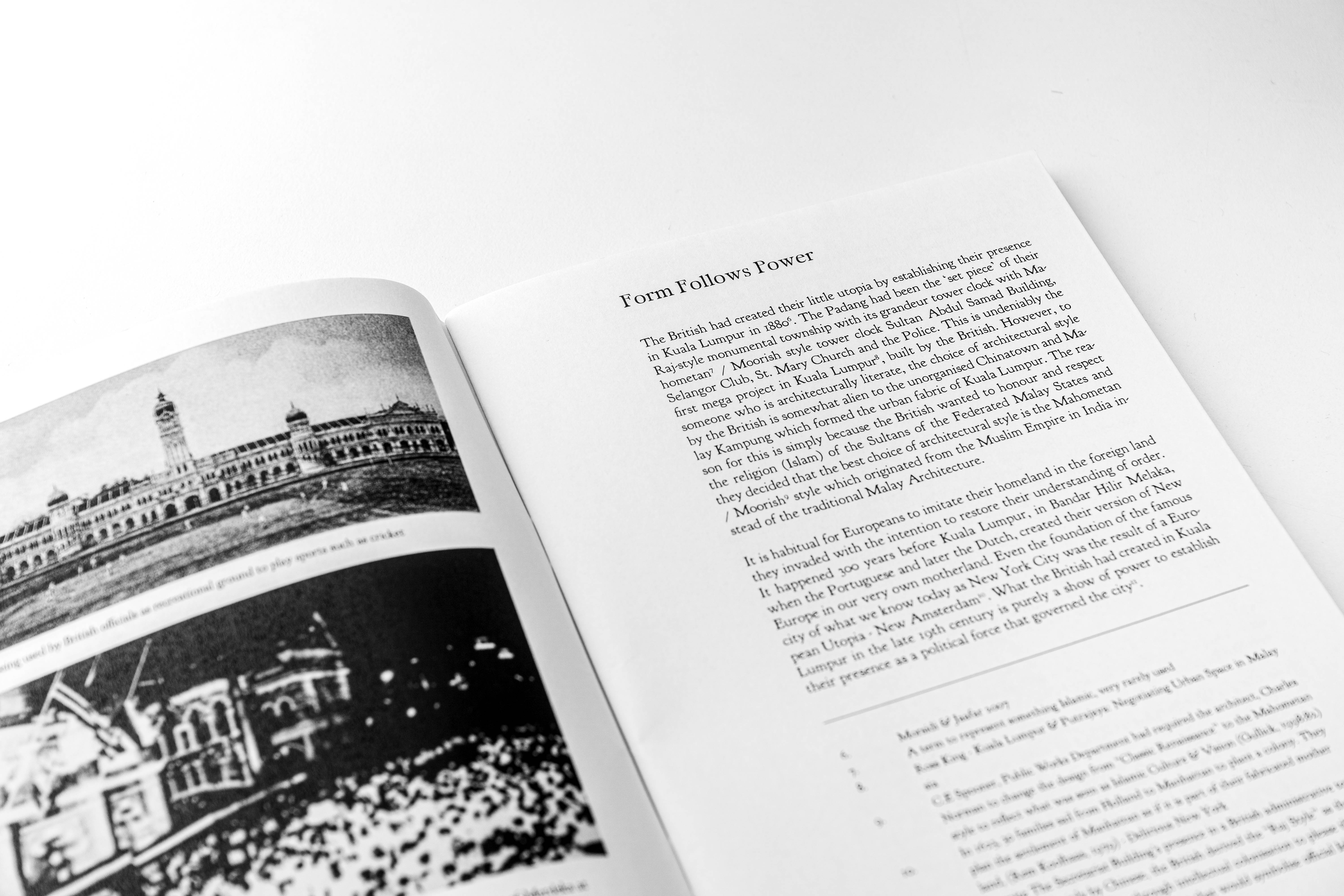

Form Follows Power

The British had created their little utopia by establishing their presence in Kuala Lumpur in 1880. The Padang had been the ‘set piece’ of their Raj-style monumental township with its grandeur tower clock with Mahometan / Moorish style tower clock Sultan Abdul Samad Building, Selangor Club, St. Mary Church and the Police. This is undeniably the first mega project in Kuala Lumpur, built by the British. However, to someone who is architecturally literate, the choice of architectural style by the British is somewhat alien to the unorganised Chinatown and Malay Kampung which formed the urban fabric of Kuala Lumpur. The reason for this is simply because the British wanted to honour and respect the religion (Islam) of the Sultans of the Federated Malay States and they decided that the best choice of architectural style is the Mahometan / Moorish style which originated from the Muslim Empire in India instead of the traditional Malay Architecture. It is habitual for Europeans to imitate their homeland in the foreign land they invaded with the intention to restore their understanding of order. It happened 300 years before Kuala Lumpur, in Bandar Hilir Melaka, when the Portuguese and later the Dutch, created their version of New Europe in our very own motherland. Even the foundation of the famous city of what we know today as New York City was the result of a European Utopia - New Amsterdam. What the British had created in Kuala Lumpur in the late 19th century is purely a show of power to establish their presence as a political force that governed the city.

After independence, Tunku Abdul Rahman as the first Prime Minister of Malaya had built several important national monuments including Masjid Negara and the Parliament Building. As a new democratic and independent country, Tunku intended to adopt a fresh approach towards development, far from the image the British colonials, hence a progressive non-ethnic centric image of Malaya was portrayed by these two projects which was inspired by Late Modern Architecture with a tropical twist. However, during the 1980’s, this modern progressive image was replaced by foreign eclectic revivalism style mostly inspired by the grandeur of Middle Eastern architecture. The politics behind this switch of direction was because of Malaysia during this period wanted to be portrayed as the model of a progressive Muslim country. The vision goes beyond Malaysia as a democratic country; the political power wanted the Muslim World to acknowledge the presence of Malaysia as a strong, democratic and developed Muslim Country on the global stage. Nonetheless, this new so-called ‘identity’ has been corrupting the minds of most Malaysians officials and even private officials and slowly taking away the power of the critical architects. Instead of having architects to lead in creating critical discourse in architecture, the paymasters are the ones taking the leading role of shaping what the country needs and what ‘style’ should we profess to show our ‘identity’. The legacy of this period can be seen everywhere around us from the most expensive government buildings in Putrajaya to the buildings of municipal councils and even in the smallest, less developed towns of Malaysia. The style had mutated from the idea of naive Eclectic Revivalism (Post-Modernism) to a vocabulary of grandeur and magnanimity to represent power.

The normalisation of this culture had impacted the way policy-makers make decisions on national projects such as the Dataran Merdeka project in 1990. According to Ruslan Khalid, the architect for the project who had begun working on it since 1987, the scheme he had proposed was totally different from what it is today. It was never his intention to build the world’s tallest flag pole as part of the Dataran Merdeka project. Instead, his main intention was just to create a space for public to come together for ceremonial and recreational purposes. He had an idea which was inspired by Ying and Yang; representing the complementary duality in our everyday life. The scheme which he proposed had sculpted monolith monument as a centre piece with a proposed Merdeka Museum underneath it. The northern end was originally designed as a meditative garden to be adorned with shady topiary trees and shrubs surrounding a large pool. Based on the design as described by Ruslan Khalid himself, his proposed design seems promising and potentially could have been the most important public space in Kuala Lumpur for years to come. Unfortunately, the idea of the centrepiece monolith was later questioned by the Mayor with the supposed intention of trimming off the cost of the project to a bare minimum. As a compromise, he suggested that a modest flagpole to be used instead, although it would not have the same impact as the proposed monolith. However, after revising the flagpole in place of the monolith, the Mayor seems unimpressed with the idea and hence the tallest flagpole in the world was proposed by the Mayor himself. To make things even worse, the project was later directly awarded to a private developer to continue with the works, and all finishes and design elements were compromised to allow for the most important ‘design feature’ of the project - the tallest flagpole in the world

The Death of Neoliberal Cities

Fighting for true democracy would be meaningless if one does not understand the struggle of living in a neoliberal city. The urban commons and urban goods which are basic citizen rights to the city are slowly vanishing from the city we live in today. As aptly written by Albert Pope in his book, ‘Ladders’, the city of today is not the ancient city or the medieval city that is inherited to us from our ancestors but the city of today is in fact, a city that we constantly build upon. These cities that we are rapidly building is a city of isolation, sugar coated with the temptation towards hip and funky lifestyle as seen through the development of gated and guarded condominiums, money-making shopping malls, business parks, classy private school and colleges and even manicured, privately-owned recreational parks. This is the reality of the life that we are living in. They are killing off the urban commons because for them, the commons are dangerous, derived from the stigma that social housings create rebellious behaviours and rebellious working class citizen. To them, the commons are an eyesore to the shiny happy image of the city that they promote in the tourism brochures. But the truth is, there are people who are struggling just to put food on the table, these people need the commons to demand for their rights and voice their thoughts. The cases of Syntagama Square in Athens, Tahrir Square in Cairo and the Plaza de Catalunya in Barcelona shows public spaces that have been reclaimed as urban commons as people assembled there to express views and make demands.

The occupy movement against ‘The Party of Wall Street’ is an example on how the people revolt against the capitalist system. Even though nothing much has changed since then, it has successfully demonstrated people’s social power and architecturally it shows the importance of reclaiming urban commons to be utilized for such purpose. It is important to note that reclaiming the Padang does not necessarily mean constant demonstration and protest. It simply means allowing the general public to freely use the space for whatever communal activities they wish. If they were to demonstrate their rights, the demands that the people should be making is to have more rights to reclaimquality public space, more affordable housing in the city, and efficient public transportation as means of commuting for the general public. It strictly should not be manipulation of urban commons and urban goods as means of exploitation, speculation and tools for greedy capitalists to further rule Kuala Lumpur as a Neoliberal city.

As what is still happening now, heritage buildings in the heart of our city which act as urban artefacts are either thorn down for high-rise buildings or being preserved only to be gentrified for value creation purposesfor maximum profit. This happens in Kuala Lumpur and most other major cities in the world where city building is not for people to live in but for people to invest in. Reclaiming the Padang in this case isbotha symbolic gesture to change anda starting point for better things to come. The Padang shall only be called a ‘padang’ when it is surrounded by a group of buildings and occupied by people, hence the need for a good mix of central urban population. Unoccupied shop lots upper-floors, and empty high-rise buildings could possibly be re-generated into new possibilities of gaining central city population. This population shall be the main user of the urban commons, followed by people who live around Klang Valley and lastly tourists and visitors. However, to prevent the likes of greedy developers and property speculators gentrifying the areas for profit, the project should purely be a government-led initiative with the intention to provide decent homes for the people.

Architecture or Revolution

After quite a thorough analysis of the current state of the Padang we had identified few issues that need to be addressed and even rethink in order for us to move forward. Architecture inevitably needs revolution, and there are many attempts of igniting this revolution previously even though the definition of this architectural revolution might differ from one architect to another. Le Corbusier in his book ‘Towards a New Architecture’ which its original title was ‘Architecture or Revolution’ (which makes a better title for the book) talks about this idea of a new kind of architecture totally detached from the ideas of the classical period. In today’s contemporary architecture, we see a lot of experimentation of funky forms, styles, and aesthetics which at the end of the day did not revolutionise anything.

The nature of the profession and the building industry remains at status quo, totally dependent on huge government and corporate contracts or private client with a thick wallet. We see this current state of contemporary architecture as an opportunity for us to potentially revolutionise how we practice architecture and create architectural projects - where architectural projects are based on series of critical thoughts and intellectual discourse involving people from different professional backgrounds and social status. This force of like-minded people could potentially call for a more transparent process of ‘nation-building projects’ free from corrupted practices.

Planting Hopes

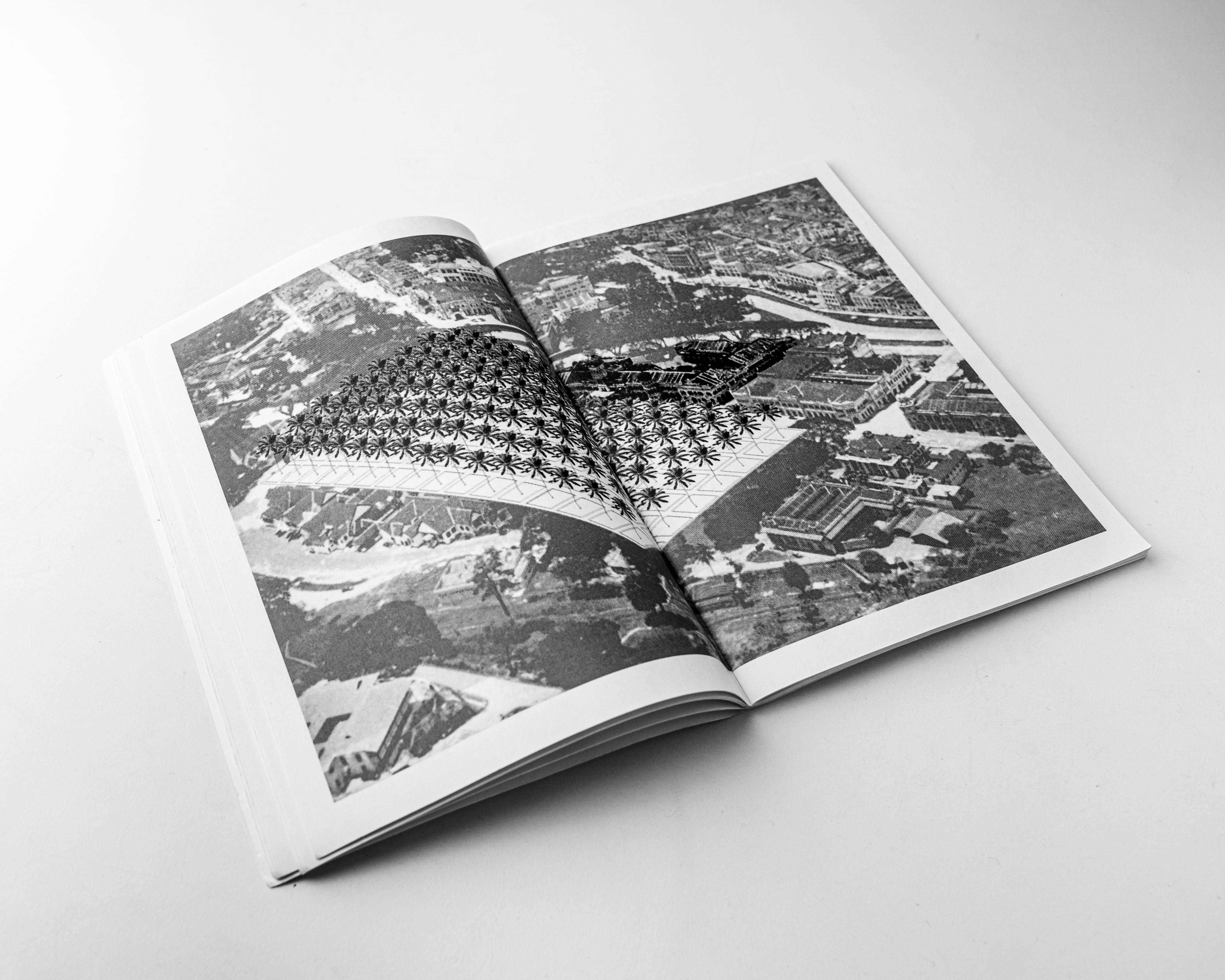

As a response to the ideas from this essay, we intend to propose a fictional project to demonstrate our expression on what could possibly be an alternate ‘padang’ as urban commons for the people and initiated by the people. The current state of Dataran Merdeka as it is today is not physically out of order, however it lacked ‘soul’. The activities conducted are too tourist-oriented and occasion-centric rather than purely an urban common for the people. The fact that the recently ‘rebranded’ Dataran Underground failed to revive the place as a prominent public space proved that consumerism is not always the answer to everything. We propose a simple act of planting rows of trees in a grid iron form symbolising a positive hope for a better future. The nature of the project itself revolutionise the conventional way of doing a project. Funding for the project could be crowd-sourced from like-minded organisations, individuals and even the government (if they wished to). The inspiration here is to revisit the true spirit of democracy like what happened on 31st August 1957.

We would love to see people eagerly coming together to participate with something really meaningful for the nation. It is about making history by freeing the people’s minds, not just another series of events and formal occasions in the form of celebrations to commemorate Merdeka. The act of planting trees on the Padang itself represents reclaiming what was previously taken by the British from the people. Before the British took over the land, the area was the place where locals planted trees and vegetables for their own consumption. More importantly the space will continue to manifest the true spirit of independence where knowledge is celebrated, freedom of speech is practised, and the right to the city were given back to the people. Activities such as public forums and debates discussing critical national issues should happen freely without intervention. Maybe as a nation, we had focused too much on physical developments but not enough on the spiritual development of the people. Moving from a developing nation to a truly civilised and developed nation, the progress of the people is much more important than the advanced physical infrastructures. This is truly our belief, that architecture is not necessarily about building the physical but it is more importantly, about the spirituality of the built environment - the non-buildings.

David Harvey. (2013). Rebel Cities from the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution.

Rem Koolhaas. (1979). Delirious New York.

Albert Pope. (1995) Ladders.

Ruslan Khalid. (2013). Quest for Architectural Excellence.

Tajuddin Mohamad Rasdi - Malaysian Architecture Crisis Within.

Pertubuhan Akitek Malaysia. (1976). Guide to Kuala Lumpur Notable Buildings.

Nor Zalina Harun and Ismail Said (2008) Morphology of Padang: A case study of Dataran Merdeka, Kuala Lumpur.

Chandran Jeshurun. (2004). The padang; Kuala Lumpur in Kuala Lumpur; corporate, capital, cultural cornucopia. Arus Intelek Sdn.Bhd. pp. 117,118 & 119.

Child, M.C. (2004).Squares: A public place design guide for urbanists. USA. University of New Mexico Press.

Gullick, J.M. (2000). A history of Kuala Lumpur 1857-1939. Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic.

Star Publications (Malaysia) Bhd. (1983). Malaya - A Retrospect of the Country Through Postcards.

Major David Ng (Rtd) & Steven Tan. (1987). Kuala Lumpur in Postcards 1900 - 1930.

Pertubuhan Akitek Malaysia. (1990). 1890 - 1990 100 Years Kuala Lumpur Architecture.

Ross King - Kuala Lumpur & Putrajaya: Negotiating Urban Space in Malaysia.

Arkib Negara Malaysia.